The Adulterous Sins of Our Father Figures

Several years ago, my mother’s partner sent me an e-mail confessing to an emotional affair. He wrote that although he and my mother were breaking up, he wished to remain my friend.

I reminded him that his infraction had been with a woman 30 years his junior. (My mother had already told me about it.)

“I expect more,” I wrote to him, “from a feminist and an intellectual.” We didn’t stay in touch.

His infidelity, such as it was, seemed to me to confirm a truth I had long held as gospel: in matters of the heart, never trust a male over 50. Men raised before second-wave feminism — that is, men born before 1960 — were deformed by a culture that regarded romantic indiscretions as natural expressions of manliness, an alternative to hunting. My antipathy spilled the banks of the personal into the ideological; I felt that the problem with these men was the problem with America. Like our carbon-greedy nation, ruining the global climate for everybody, they suffered from a belief that they deserved what they wanted, no matter the collateral damage.

I was not the first person to draw a comparison between American consumption habits and the romantic greediness of middle-aged American men. There’s a scene in John Updike’s novel “Rabbit at Rest” in which a Japanese businessman complains to Rabbit Angstrom, a veteran adulterer with designs on his daughter-in-law, that Americans believe “freedom” includes the right to let their dogs defecate on the sidewalk and not clean it up. In Jonathan Franzen’s novel “Freedom,” Walter Berglund, an environmentalist born late enough to grow up with the women’s movement, reflects that his lust for his young assistant threatens to turn him into yet another “overconsuming” white male.

My great goals for myself in my 20s included not becoming an Updike protagonist and not becoming one of the middle-aged men I grew up around. I used the older generations of American men as an extensive negative example.

My religion, I decided, was mindful self-loathing. If you’re born Caucasian, male and middle class in the United States, your job is to check the manifestations of the entitlement bred into you by your native culture. These manifestations pop up continuously. Whenever I was tempted to flirt with somebody I wasn’t supposed to flirt with, or indulge in some other depravity, like driving when I could take a train, I would think, “Don’t be a disgusting white guy like Stepfather Figure X.”

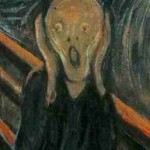

This ethos brought with it the thrill of hatred — and danger. When you despise a class of people, the notion that you might become that which you hate in a moment of moral frailty is frightening in proportion to the intensity of your contempt. And the anxiety worked; I never cheated on anybody. My reward was a feeling of moral superiority that emerged when I wasn’t busy nursing my self-loathing. Smugness and self-suspicion circled like a moon and sun, one climbing in the sky as the other fell.

And then, at 30, a month after I wrote the bitter e-mail to my mother’s partner, I ran into an ex in front of my gym. We stood there blinking at each other. She said something to the effect of, hello, favorite ex-boyfriend. I found this remark endlessly beautiful. But I was in a committed relationship. Don’t be a piggish middle-aged white guy, I thought.

“I’m wearing one of your old gym shirts and you’re wearing one of my old gym shirts,” I said, feeling that this was a proper, truthful, chaste and unavoidable observation. Two seconds later, we were holding hands and walking toward a bench. Twenty seconds later we were kissing on that bench. The next evening, we met for coffee, to process, I told myself, the fact that we had kissed on a bench. We ended up making out in my car.

There followed an epoch of self-disgust. My transgression would probably hurt my girlfriend worse than my mother’s partner’s had hurt anyone. And the excuses he made to himself were probably as persuasive and self-infantilizing (“It happened so fast!”) as the excuses I made to myself. What was worse than the repulsion I felt at my behavior was the sense of exhilaration that lurked beneath. I realized that I liked having it both ways; it was fun to be a cheater who moralized.

There followed an epoch of self-disgust. My transgression would probably hurt my girlfriend worse than my mother’s partner’s had hurt anyone. And the excuses he made to himself were probably as persuasive and self-infantilizing (“It happened so fast!”) as the excuses I made to myself. What was worse than the repulsion I felt at my behavior was the sense of exhilaration that lurked beneath. I realized that I liked having it both ways; it was fun to be a cheater who moralized.

So what do you do when you discover you belong to a class of men you hate? Suicide, like cheating, inflicts suffering on anyone unfortunate enough to love you. And self-loathing, my reliable spiritual practice, had failed me in front of the gym.

The problem with self-loathing, I realized, is that you can’t maintain it forever. If you fool yourself into thinking that you despise yourself thoroughly and uninterruptedly, your selfishness, which is to say your self-love, sneaks up on you. As long as you’re committed to staying alive, you should try to be a friend to yourself, albeit a skeptical friend, in order to do less harm. Hating yourself is a kind of stimulant, anxiety-producing but also energizing. It can be nearly pleasurable. I found I had to kick that stimulant in order to act morally.

I broke up with my girlfriend, although I never told her about the bench or the car. I wrote a novel about two teenagers, a boy and a girl, who catch the boy’s father and the girl’s mother necking in a supermarket. Furious, they sign a vow never to cheat on anybody, and have no trouble keeping it until they meet again at 28, both engaged to other people. In the process of falling for each other, they fall, at first, in their own estimation. But they come to like their cheating parents better than they did before. Put simply, they learn mercy.

Mercy: that might be the singular benefit of repeating the sins of the previous generation. You might learn how quickly desire can rout ideology. You might acknowledge that you are not wholly unlike the dream-home-building, car-loving Rabbits you define yourself against, in that your major life decisions are guided by wants and not beliefs. Once you stop hating yourself, you might hate other people less.